“[…] [C]onnecting works of art with objects which are not exclusively functional, but also possess a mental, spiritual, religious or sacred scope, which also have, compared to everyday objects, what you call an aura. “Magician” refers to mental activities. It is not the literal meaning of the word that must be taken here, but the one you commonly use to speak of ‘the magic of art’.”[1] Jean-Hubert Martin, instigator of the 1989 exhibition “Magicians of the Earth”, held at the Grande Halle de la Villette and at the Pompidou Centre, commented in these words on his wild curatorial gamble to display a selection of non-Western artworks from different cultures. But if his show already included Aboriginal creations, testifying to the Western audiences’ rising interest in and taste for the Aboriginal pointillist motifs, it did not single Aboriginal art forms out as the astounding, recently closed exhibition “Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art” at the Musée du quai Branly (Paris, France), did over the past few months.

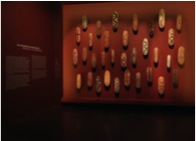

Celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Papunya Tula movement’s birth, started in 1971-1972 near Alice Springs, curators Judith Ryan and Philip Batty proposed an unprecedented approach to Aboriginal art in France. The 200 works and 70 objects displayed in the recently closed exhibition at the Musée du quai Branly recounted the rise and evolution of the multifaceted, first Aboriginal works carried out on perennial materials, taking the origins of the Aboriginal painting tradition as its entry point. Thus prominently hung against rails painted in dark ochre shades reminiscent of the Great Sandy Desert, traditionally ornamented shields, weapons or headbands (fig.1) welcomed the visitors. Over each object, subtly orchestrated motifs unfolded in harmonious compositions all associated with stories of the Tjukurrpa (Dreaming). These ancient motifs would prove to be central to the Aboriginal visual culture in the following rooms specifically devoted to the Papunya artists, where visitors could admire them at leisure, for they were omnipresent in the exhibited works.

Indeed, the recurring patterns of concentric circles (waterholes, rock or encampment), U shapes (seated figures) or sinuous lines (reptiles’ tracks, water streams or yam roots) have been used for millenaries to tell the narratives of the Tjukurrpa. By drawing these motifs on the Desert sand, on rocks or wooden poles, Aboriginals re-enact their Ancestors’ great deeds, mapping the latters’ mythical journeys through the Australian land and conjuring up their presence.

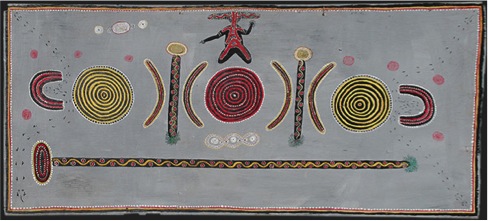

Fig.2 – Kaapa Tjampitjinpa (Anmatyerr/Warlpiri c.1925-1989), Men’s Ceremony for the Kangaroo, Gulgardi, 1971 – 61.0 x 137.0 cm

© Artists and their estates 2011, licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Limited and Papunya Tula Artists

From the first acrylic paintings of 1971-1972, such as Kaapa Tjampitjinpa’s Men’s Ceremony for the Kangaroo[2] (fig.2), directly inspired by a dream whose custodians were Kaapa’s family members, one discovered the oneiric world of the Papunya Tula paintings, a world saturated with natural colours, symbols and significance, and followed its evolution, year after year, up until the culmination of the last gallery and the monumentality of the 1990s formats (fig.3).

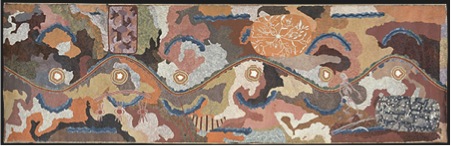

Fig.3 – Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri (Anmatyerr c.1929-1984) and Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri (Anmatyerr c.1932-2002), Spirit Dreaming through Napperby country, 1980 – Synthetic polymer paint on canvas – 207.7 x 670.8 cm

National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Felton Bequest, 1988 – (O.33-1988)

© Artists and their estates 2011, licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Limited and Papunya Tula Artists

The show, structured around a chronological path, mirrored the Aboriginal initiation process: it had the visitors embark on a journey made of successive aesthetical stages, spatially and thematically echoing initiatory ritual practices. The sequence of rooms, at the expense of explanatory labels that would reveal the sacred, secret meanings of the painted designs, functioned along evocative, rather than descriptive dynamics, to conjure up the dreamlike atmosphere of the Aboriginal cosmology (fig.4). Overcoming the pitfall of a strictly anthropological perspective which would have focused on utilitarian or ritualistic aspects solely –and which one could have feared upon seeing the film documenting Warlpiri fire ceremony or Paul Exline’s photographs upon entering the exhibition space–, the show actually took into consideration the artistic quality of the works. By acknowledging this pluridimensionality of Aboriginal art forms, where multiple levels of spiritual and temporal significance are embedded, the curators invited the onlookers to a sensory, emotional encounter with the first Aboriginal acrylic paintings. To that extent, the exhibition successfully served as a threshold, a window opening onto Aboriginal art.

However, the choice of showing without explaining presented some risks, notably that of arousing an impression of frustration. Indeed, the majority of the French visitors were not particularly familiar with the Aboriginal iconographic repertoire; consequently, some may have thought it was a shame to place the wall-panel providing some reading-keys for one to decipher the depicted symbols, halfway through the tour rather than in the first rooms of the show. Similarly, the feeling of privilege one experienced upon being ushered into a secret recess –where works rife with strictly male secrets were for the first time disclosed and shown to both Western uninitiated and female visitors– mixed with one of disappointment, with the feeling that the possibility of true understanding and of opening fresh perspectives was restricted to a small élite of connoisseurs. Unequipped, common viewers were hence left with the beauty of the exhibited works –nonetheless deeply enjoyable for their own sake– and possibly frustrated expectations. Without asking for the flouting of Aboriginal transmission traditions, which necessarily deny complete access to certain aspects or elements of the Dreaming to members of the opposite sex and neophytes, further explanations, possibly on narratives and dreams which the Aboriginal Senior figures have already agreed to reveal to non-Aboriginal audiences, would have made the overall exhibition more accessible to those who discovered Aboriginal art for the first time.

On the other hand, by opting for a suggestive approach, at the expense of descriptive labels, but resolutely in tune with Aboriginal laws, the curators put the visitors in the exact same position as an Aboriginal child who is about to undertake his or her initiation. As a result, one’s desire to learn more about the Aboriginal culture was enhanced: the French audiences’ enthusiastic response to the show crystallized in the quick selling out of the whole stock of catalogues.

Regrettably –and puzzlingly enough– only very little mention was made of the importance the intrinsic, musical quality of the painted works: to tell a dream, Aboriginals draw, but they also sing. Their works are both painted maps tracing back the paths the Ancestors took through Australia, and scores of the song lines these mythical tracks constitute. Musical animations would have certainly been much appreciated by the public. In the same way, the programmatic title “Origins of Western Art” contained the promise of the illumination of current creations by the Papunya Tula paintings, through the combined displays of early and more contemporary works. It was unfortunate that works carried out by contemporary, and also by female artists –whose contribution to the promotion and passing on of Aboriginal representational tradition is invaluable– should have been totally absent.

The “Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art” exhibition, thus oscillated between extensive documentation on the Papunya Tula movement, in the form of the works themselves and of artists’ biographies, and the sparing of cultural sacred secrets and mysteries. Despite the potentially discouraging lack of information on the particular significance of each work for non-initiate visitors, the show, which was the very first one to be specifically devoted to Aboriginal artistic creation in France, was a huge success, meeting the challenge of showing and promot

Bénédicte Vachon, IDAIA’s Representative and Curator in France

[1] IDAIA’s translation. « [R]elier des œuvres d’art et des objets qui ne sont pas purement fonctionnels, qui relèvent du mental, du spirituel, du religieux, du sacré, et qui ont, par rapport à des objets quotidiens, ce que nous appelons une aura. ‘Magicien’ fait allusion à des activités mentales. Il ne faut pas prendre le terme dans son sens littéral, mais de la manière dont on parle couramment de ‘magie de l’art’ », in Geneviève Breerette’s article entitled « Oser regarder, vouloir s’étonner – Rencontre avec le Responsable de l’Exposition », LE MONDE – Arts Spectacle : Supplément, 18 Mai 1989, pp. 127-128

[2] This very work enabled Kaapa Tjampitjinpa to jointly win, in September 1971, the Caltex Art Award in Alice Springs; it was instrumental in shedding light on and promoting the Papunya community’s artistic creations.

About the Author:

Bénédicte Vachon is IDAIA’s Representative and Curator in France.