IDAIA – International Development for Australian Indigenous Art, in collaboration with ACM and New Angles, presents a double exhibition which showcases artworks by the rising Aboriginal painter Lydia Balbal for her first solo exhibition overseas, as well as significant paintings gathered in the show Strong Women Country and celebrating the art of female artists.

Context

A historical exhibition is about to open at the Musée du quai Branly. Originating from the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, the exhibition “Tjukurrtjanu: Origins of Western Desert Art” is exclusively hosted by the Parisian museum from October 9th, 2012 to January 20th, 2013. It celebrates the 40th anniversary of the Papunya Tula movement, starting point of the contemporary Aboriginal acrylic painting. This groundbreaking exhibition gathers over 200 paintings and 70 objects, including some of the first artworks created by the very artists who initiated this movement in the 1970s.

On this special occasion, IDAIA proposes three simultaneous exhibitions, with distinct scopes and contents, but all designed towards a single objective: offering an alternative and contemporary perspective in response to the Musée du quai Branly exhibition.

Synopsis

Organised with ACM and New Angles, the exhibition unfolds at the heart of the Passage du Grand Cerf in a multi-level space, allowing for the creation of different atmospheres, different perspectives, to testify to the diversity and vitality of Aboriginal art.

The main space is devoted to the luminous and bold creations of rising star Lydia Balbal, for her very first solo exhibition outside of Australia. Born around 1958, the Mangala artist based in Bidyadanga has already had 5 solo shows in Australia. Parallel spaces celebrate the art of significant female artists, from Warakurna and Martumili to Bidyadanga, also represented by Jan Billycan and the late Weaver Jack, to Yirrkala in Arnhem Land with a tribute to the late Gulumbu Yunupingu.

Lydia Balbal

Lydia Balbal was born around 1958, in the remotest part of the Great Sandy Desert, near Punmu. She spent her childhood in these ancestral lands, untouched by exterior civilizations, until 1972, when her family left the desert to settle at the La Grange Mission, in the coastal town of Bidyadanga.

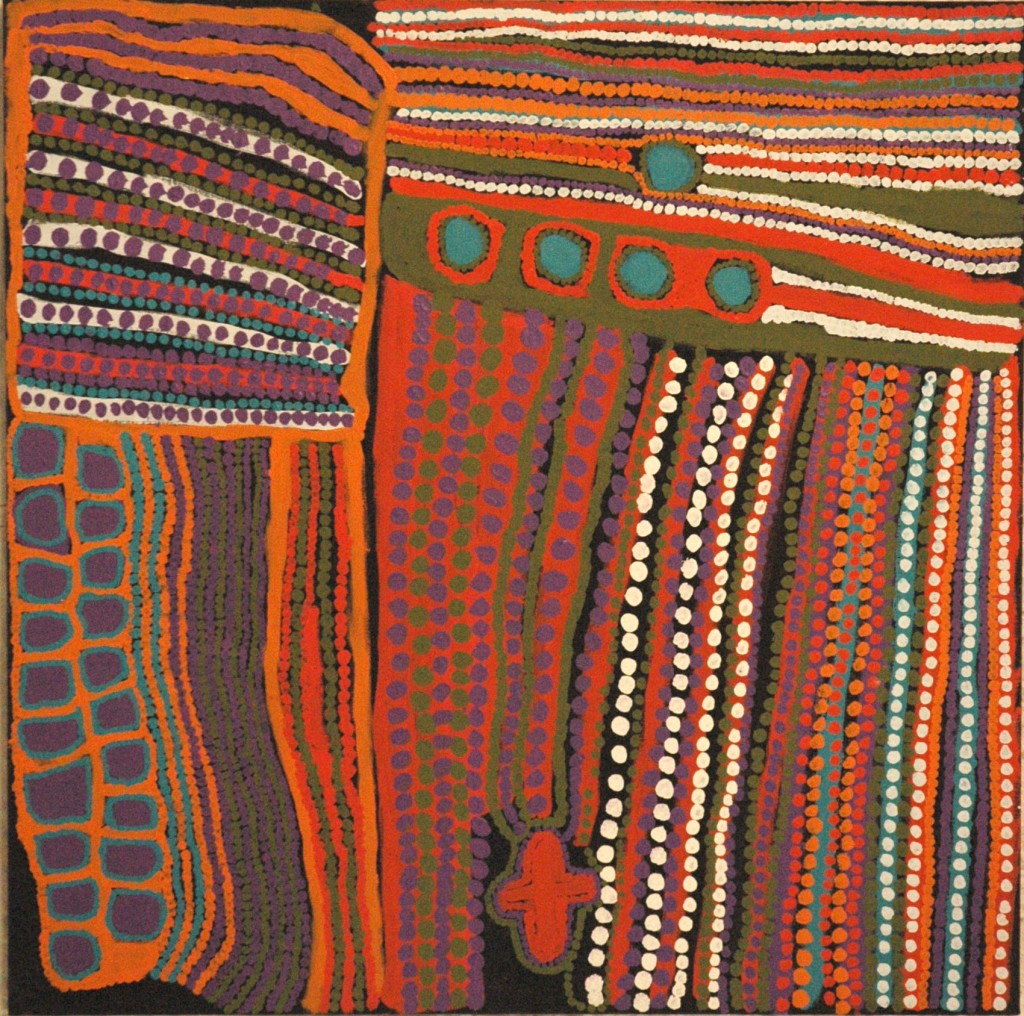

Although Lydia witnessed the rise and development of the Bidyadanga community painting movement from its beginnings, she only started painting in 2007. Despite her being today in her mid-fifties, she stands out as an emergent, resolutely modern and avant-garde Aboriginal artist. Her work is characterized by a unique combination of ancestral traditions with novelty. Lydia’s paintings hold together on her canvases the strength of the desert age-old wisdom, knowledge and mythical beliefs –of which she is the guardian– and the freeness and assurance of the bold chromatic contrasts and individual aesthetics she elaborated.

Indeed, if Lydia depicts the desert country and imbues her works with traditional symbolism, she detaches herself from her Bidyadanga predecessors by adopting a radically new perspective, shaped by her (hi)story. “I’m painting underground,” she once explained. “What’s underground. Upside down: water, rockholes, lines beneath the sand-dunes.“[1] What Lydia proposes is a differentiated experience of place. She recomposes traditional landscapes from beneath: mimicking the course of subterranean water streams, or the process of digging into one’s memory, her creative acts are ones of exploration, reaching for the roots of thousand-years-old myths and landscapes, going beyond the mere visible surface of things.

Lydia’s mesmerizing expanses of colour which sensuously unfold before the beholder’s eyes are pregnant with desert motifs of rockholes, brown snakes, and hunting memories. By pouring out vibrant reds, deep, earthy oranges and greens with softer hues, this virtuoso colourist takes the viewer on an emotional journey through the vastness of desert sceneries, catching him/her up in her canvases.

Unsurprisingly, her work has been crowned with success and she has been receiving, since her recent debut, significant praise and recognition from collectors and art critics alike. She already had 5 solo exhibitions in Australia and some of her works form part of major public collections in Australia and the Netherlands.

A number of the artworks exhibited in the Passage du Grand Cerf were previously displayed in the exhibition “remix”, held at the Art Gallery of Western Australia in 2011. Significantly, the show promoted the creations of contemporary Australian artists and aimed at unveiling the very making of artworks. This première on the national artistic scene was, for Lydia, a step further in her being acknowledged as a figurehead of the Australian contemporary creation. It testified to the impact of her work on today’s perspectives on Aboriginal art.

Strong Women Country

The paintings of the female artists exhibited together with Lydia’s also reveal the artists’ intrinsic link with their land. Their works associate an intimate knowledge of the desert landscape with the rich colours of the salt water country, resulting in unique a pictorial style. As pointed out by Judith Ryan, Curator of Aboriginal art at the National Gallery of Victoria, the desert women “have an amazingly strong cultural memory which comes out in the extraordinary colours and with this incredible exuberance and spontaneity.”[2]

This exhibition was orchestrated to achieve a double objective. It first aims at opening a window, from the Western world, onto contemporary female Aboriginal art, and to serve as a threshold enabling inter-cultural conversations and reciprocal exchanges. But it also is a poignant tribute to recently deceased artists, such as Gulumbu Yunupingu or Weaver Jack, who were leading spiritual figures and inspiring artistic guides.

Gulumbu Yunupingu (c. 1945-2012) belonged to the Yirrkala community, located in Arnhem Land, and whose artists are famous for their bark paintings. Gulumbu, who had studied to become a health worker and possessed great knowledge of bush medicine and plant uses, was actively involved in the mutual enriching of Aboriginal and Western cultures –she was one of the four translators of the Bible into Gumatj. She remarkably promoted dynamics of cross-fertilization in contemporary artistic creation. When in 2004, the Musée du quai Branly in Paris launched its institutional project of architectural decoration, she was one of the eight indigenous artists who were invited to participate and create a work specifically for the museum. Unveiled in 2006, the ceiling she painted remains a strong visual testimony of her intellectual and artistic beliefs. For all these reasons, her being displayed among the female artists presented here, finds particularly strong resonances with the overall concept of the exhibition ‘Lydia Balbal + Strong Women Country’.

Weaver Jack (c. 1928-2010) came, like Lydia Balbal, from Bidyadanga, where she was considered to be a senior law woman and spiritual guide among the Yulparija people. She was one of the founding members of the pictorial movement of Bidyadanga, starting experimenting with acrylic on paper and then on canvas in 2003. She quickly emerged as a master colourist, and in 2006, she became the first indigenous artist to be awarded the Archibald Prize, Australia’s most prestigious prize for portraiture.

Jan Billycan (c. 1930) is a Marparn woman, that is to say a medicine woman, who was bestowed with the ability to see in X-ray – a fact which appears obvious in her works. Jan Billycan’s X-ray vision enables her gaze to penetrate the forms which she then paints on her canvases. She took part to numerous exhibitions, in Australia (to the 2007 Triennal of Australian Indigenous Art, ‘Cultural Warriors’, held at the National Gallery of Australia, ACT, for instance), but also in the United Sates (‘Bidyadanga Artists’, Harvey Arts Projects, Sun Valley, Idaho, 2010 and ‘From Desert to Saltwater’, Booker-Lowe Gallery, Houston) or in China (Olympic IOC Expo Centre, ‘Canning Stock Route Project’, 2008).

The Martumili artists – a community living in the heart of the Pilbara region, deep in the Western Australian Desert – translate in their paintings both the Martu culture and the dramatic geography and scale of their homelands, such as Lake Disappointment, the Rabbit-Proof Fence or the Canning Stock Route and its wells. The story of the Martu people has always been intrinsically linked with that of traditional tracks: this is the reason why their paintings are haunted by the recurrent theme of paths and their symbolism. Their works tell of the brutal contact with the Western world, which came to transform the traditional tracks into European roads. Whilst painting these stories, the Martu artists aim at educating the young generations and passing on their own vision of the Desert, recent and past. Established in 2006, the Martumili art centre played an important part in the carrying out of ‘The Canning Stock Route’ exhibition project which was successively welcome in Canberra, Perth and the Australian Museum in Sydney (mid-2010 to mid-2012).